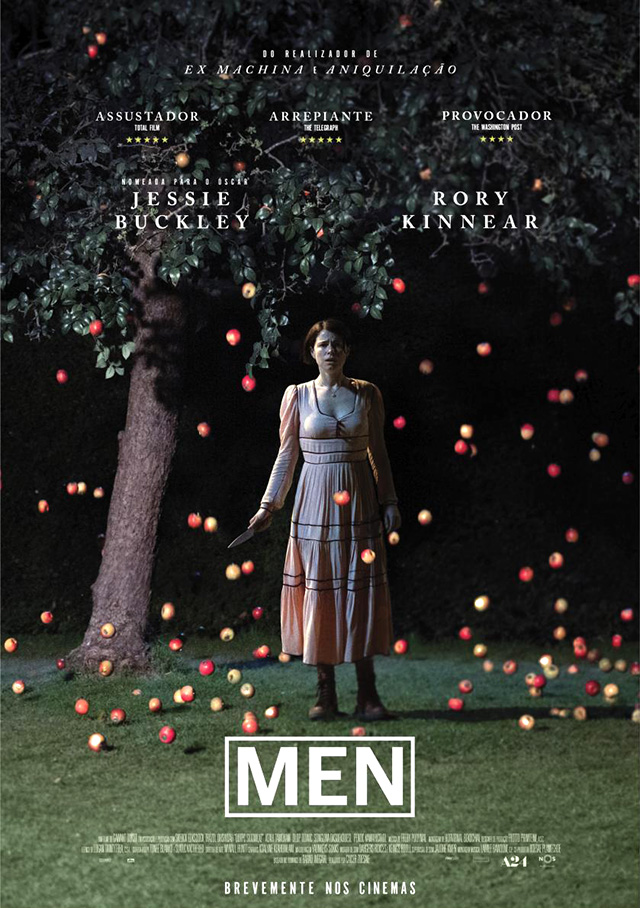

Falling forbidden fruit, the phallic knife – this allegory is laden with religious symbolism.

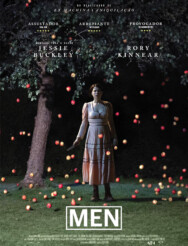

Men (2022 Film) – Insidious Misogyny

Men, a 2022 British film by writer-director Alex Garland, left me reeling and utterly spellbound. Visually arresting, emotionally raw, its psychological depth both triggering and shattering, at once magnificent and profoundly terrifying. This dark fairytale carves open the festering core of insidious misogyny, entrenched patriarchy, and toxic masculinity. trailer here

Men masquerades as a folk-horror film, but like Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining, its true terror lies not in supernatural frights but in the stark reality it unveils. Misogyny’s horror isn’t in its monsters, but in its mundanity. A relentless cycle perpetuated by men, birthing itself anew through each generation. The story follows Harper (Jessie Buckley), a Londoner retreating to the English countryside to heal from witnessing her husband’s violent death. (His fall, man’s fall from the Garden of Eden, precipitated by Harper, Eve.) Yet, this pastoral escape offers no solace, instead plunging her into a surreal nightmare where every man she encounters, all chillingly portrayed by Rory Kinnear, embody this entrenched patriarchy – essentially, all men are the same.

Far from a conventional narrative, ‘Men’ echoes the works of Peter Greenaway, demanding viewers abandon the urge to chase a tidy beginning, middle, and end. Instead, its power lies in letting its vivid, unsettling images -seep into your consciousness, stirring primal responses. Women and men may indeed experience the film differently: for women, a visceral recognition of the ever-present threat of male violence; for men, perhaps a confrontation with their own complicity or lack of awareness.

Harper’s tormentors shift through many incantations (all played by the same actor, Kinnear), but all are essentially smug, patronising, controlling, predatory. From the dippy, inept landlord, Geoffrey to a naked stalker emerging from the trees. Each encounter amplifying the film’s meditation on gaslighting and male sexual aggression. A background stress women endure daily, living every moment on alert for the next predator. Her ill-fated holiday becomes a microcosm of women’s lived reality—surrounded by men offering help that cloaks harm, their faces all blurring into Kinnear’s unsettling grin.

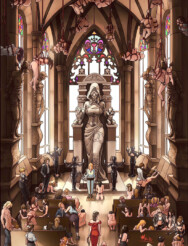

The film’s climax catapults this tension into a grotesque body horror, as Garland unleashes a ‘rolling birth’ sequence that’s impossible to un-see. Every iteration of Kinnear’s male characters gruesomely births the next through a CGI vagina erupting from their bloated torsos, a monstrous chain of men unfolding from the grounds into the house.

The film’s climax catapults this tension into a grotesque body horror, as Garland unleashes a ‘rolling birth’ sequence that’s impossible to un-see. Every iteration of Kinnear’s male characters gruesomely births the next through a CGI vagina erupting from their bloated torsos, a monstrous chain of men unfolding from the grounds into the house.

Laden with references to the Sheela-na-gig and Green Man, Mother Earth, this surreal spectacle transforms low-key menace into a full-on assault of flesh and symbolism, exposing masculinity’s unchecked mutations. It’s a visceral allegory for misogyny’s self-perpetuation, each new form as threatening as the last. The vicar’s sanctimonious victim-blaming. A police officer’s casual dismissal of Harper’s naked, bloody intruder as “harmless” sears as an indictment of the systemic failure toward victims of stalking and assault. The film’s broader point that real-world misogyny isn’t so easily spotted as these exaggerated archetypes. And, the true horror, Garland hints, lies in the ambiguity—when you can’t discern if the man beside you is saviour or villain. Or does it matter – men are men.

Harper enters a tunnel (womb/vulva) Mother Earth, the source of all life, she’s resonating and (literally) harmonising with nature, it’s magical – until the peace is shattered by (a) man’s intrusion.